Bel and the Dragon (appendix to Daniel), Jeremiah 50:2 (LXX 27:2), Jer 51:44 (LXX 28:44), Habakkuk 2:4, 1 Cor 10:19-20.

The story of Bel and the Dragon, found as an appendix to the book of Daniel, is perhaps the “hardest sell” of the Readable Books (Apocrypha/Deuterocanon) for those who do not have it in their Bible. Its whimsical and folklore-like quality has led some Protestant leaders generalize, calling the entire collection of the Readables childish and superstitious. However, for those of us who receive it, Bel and the Dragon is evidence that God uses various genres or kinds of literature to instruct us in righteousness, and engages the imagination, and even our sense of humor, rather than merely our minds. The early Church fathers knew it well, beginning with St. Irenaeus, who quotes verses 4 and 5; indeed the renowned Origen referred to it as Scripture in his Epistola ad Africanum, reminding us that the story is also found in the version of the Jewish scholar Theodotian, whose work the Orthodox have used for transmitting the entire book of Daniel. It is helpful to remind our Protestant friends that even Martin Luther included it, collected in a special section with the other disputed books, labelling this section: “The Apocrypha: Books which are not to be held equal to Holy Scripture, but are useful and good to read.”

Why, then, is Bel and Dragon “useful and good to read,” and what is there in it that gives it, for the Orthodox, a place in the canon? Let’s notice first that there are three parts to the story—the first about an idol that cannot eat (or do anything else); the second about a fierce dragon who eats and is destroyed by what he eats; the third about a God who has no need Himself to eat, but nurtures and sustains His human creatures. The entire book proceeds with the bold declaration of Daniel, as celebrated by St. Athanasius in his Discourses Against the Arians (3.30.5; CPT 173.287): “Daniel said … ‘I do not adore idols made by the hands of people, but the living God, who has created the sky and the earth and has power over all flesh.’” Daniel, like the prophet Joel, says Athanasius, has in mind particularly “the flesh the of human race”, though I suppose the story also shows that God has power over dragon and lion flesh!

The story of Bel is setup from the get-go with a light touch. Daniel (and we readers) hear the king’s boast that Bel must be living: “Do you not see how much he eats and drinks every day?” In fact, twelve bushels of fine flour, forty sheep, and six vessels of wine! An ancient commentator wryly remarks, “Ah! What a great sign of acknowledgment—that a god eats and drinks a lot!” (Pseudo-Chrysostom, On Daniel 13 PG 56:244). Daniel also smiles, and the who-done-it begins!

Like the first story of the book, Susanna, Daniel plays the wise detective, rooting out falsehood—regarding idolatry rather than adultery this time. Once the food has been laid out for the idol, he sprinkles ashes all over the floor, and seals the doors to the Temple with the very seal of the king. The stakes are high: death for the ones who are deceiving or for Daniel who is accused of blaspheming. But the 70 thieving priests of Bel and their families are unconcerned, for they have access to the Temple a secret door under its table, and chow down as usual. At the crack of dawn, the King looks in and is deceived; he seems to have forgotten about the ashes. From the doorway to the Temple, all he sees is the consumed food, and he cries out “Great are you, O Bel and with you there is no deceit at all!” Daniel’s smile turns into an outright laugh. He prevents the crime scene from being contaminated, and then points out the male, female, and children’s footprints leading up to the table. The king is enlightened and executes the culprits, but leaves the idol to Daniel, who destroys both it and the Temple. In so doing, he fulfills the words of Jeremiah: “Babylon is taken, Bel is put to shame…Her images are put to shame, her idols are dismayed.’ (Jer 50:2/cf. LXX 27:2); “And I will punish Bel in Babylon, and take out of his mouth what he has swallowed, and the nations will not flow up to him” (Jer 51:44/cf. LXX 28:44).

Bel, a major Babylonian deity, is shamed, because King Cyrus of Persia no longer recognizes this god of the land that he has annexed to his own new empire. With our Christian formation, we may fuss over the execution of the priestly families, but at least this is done by the hand of the pagan king, and not by the prophet. We might prefer a different ending, where the families repent and live: but this closing is authentic to the era in which it was written, punishing idolatry and deception in the strongest terms possible.

The second part of the tale “ups the ante.” In this story, what the dragon takes into his mouth actually destroys him from within, putting into graphic comedy the prophecy of Jeremiah that God will punish this pagan people and their monarchs who “like a dragon” have swallowed up the people of God (Jeremiah 51: 34//LXX 28:34). The king points out the dragon to Daniel, saying “Look, this one eats! He is living! So worship him.” But Daniel is again resolute, saying “I will worship the LORD my God, for He is the living God.” Indeed, in Daniel’s language, God’s mysterious name, the LORD, means “the existing One,” the One who has always been, is, and will be forever.” As God revealed to Moses, “I am who I am.”

|

It is as though the first part of the story about Bel were saying to us, “look, idols are fake, something to laugh at!” And this is a strong theme in the prophets, as well as in St. Paul’s letters—they are nothing, they cannot talk, they cannot think, they cannot act.” We see this in the ridicule heaped upon idols and idol makers in Psalms 115/14:4–8; 135/134:15–18; Isa 40:18–20; 44:9–20; 46:6–7; Jer 10:3–9; and Hab 2:18–19: “They have mouths, but speak not, eyes have they but see not, hands but they handle not, noses but they smell not, feet but they walk not…Those who make them and trust them are like them!” But now, what about the mysterious beings to which the idols point? Demons, human-eating monsters, things that go bump in the night? After all, the Devil tried to tempt Jesus, and in Revelation, there are fearsome beings that threaten God’s people. Even St. Paul, who has called the idols “nothings,” admits that food sacrificed to idols may actually be food offered to demons (1 Cor 10:19-20)!

Well, then, says our story, if you can’t just laugh at idols, but find yourself confronted by evil that seems living and strong, remember Daniel—they are not invincible, and God will destroy them through their very actions. Ravishing and eating will be their downfall. (Consider how Babylon dies, destroyed from within, in Revelation 17-18). This serpent or dragon does not even need to be slain by a staff or sword: he is his own worst enemy, and Daniel says, once the dragon has imploded, ”Behold, the things that you have been worshipping!”

In this colorful tale, the king is converted– but not his people, who complain, “the king has become a Jew,” and who threaten the king with insurrection and death unless he hands over Daniel. So, it’s back to the lions, despite the reluctant king. The new demon is the mob, clamoring for its old ways, and refusing to see what is before their noses. Of course, the drama is high, featuring seven lions that have been left hungry, and Daniel’s sojourn in the den with them for seven whole days. But this time the problem does not appear to be Daniel’s safety from the lion’s mouth—after all, everybody has already seen the angels shut those mouths. No, it is Daniel’s hunger.

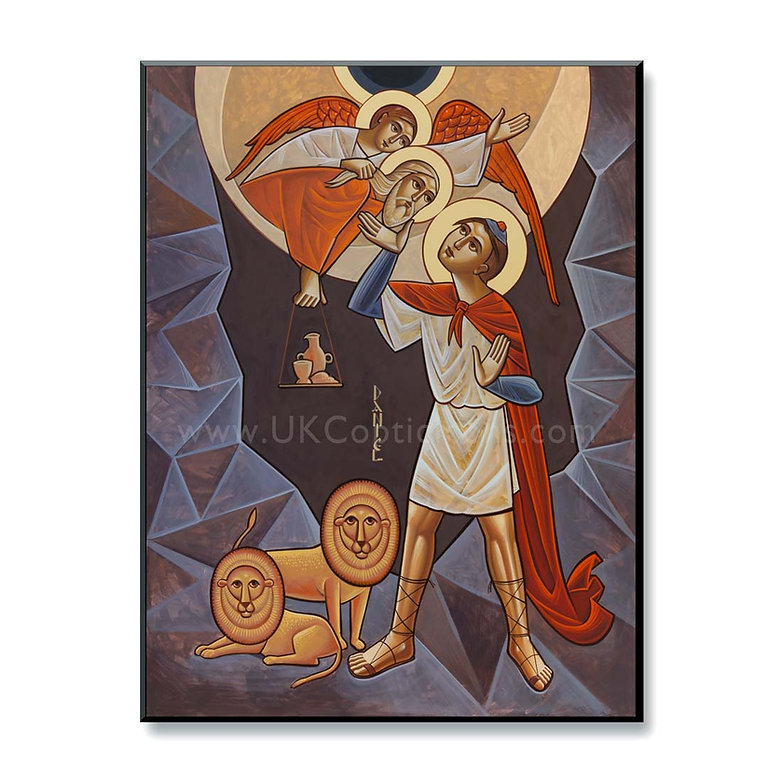

And so, while Daniel languishes, the prophet Habakkuk, miles away and living a century or so before Daniel, is preparing a meal of stew and bread for those hard at work reaping in the fields. The angel of the Lord tells Habakkuk instead to take this meal to Daniel in the Babylonian lion’s den. But Habakkuk knows nothing of Babylon or the den. No problem! The angel transports him by the hair of his head, and we behold a celestial meals-on-wheels, for which Daniel is grateful: “You have remembered me, O God, and You have not forsaken those who love You.” So there, in the presence of his feline and human enemies, God prepares a table for his prophet, and the angel takes Habakkuk home. The king then arrives to mourn over Daniel, but finds him alive, and cries out “Great are You, O Lord God of Daniel, and there is no other besides you.” Of course, the king punctuates his praises with his customary blood-thirsty judgment, and casts into the den to be devoured those who had plotted against Daniel.

Why Habakkuk? We can think of several reasons. First, Daniel was keeping kosher, and where better to get an approved meal than from a Judean prophet? Next, of course, Habakkuk, like Daniel, had scorned idols, and foresaw a dark future in which God’s people would have to hold firm: “though the fig tree will not bear fruit…and there be no oxen in the cribs, yet I will glory in the LORD. I will rejoice in God my Savior. The Lord God is my strength…He will set me upon high places, so to conquer by His song” (Hab 3:17-19). In Daniel’s story, Habakkuk is not only put in high places, but is brought throuh them to Daniel, in the lower places of the earth, to strengthen him. We have seen how Daniel’s friends in this book conquer by singing the song of the Lord (The Song of the Three Youths). And now we are again reminded of God’ sustenance even in the bleakest of times. Let’s remember that Daniel, read in fullness in the Greek version, begins by introducing the youth Daniel who can solve the mystery of the elders’ wicked lies against righteous Susanna. God knows all about enemies within His own community, and has this in hand. In Bel and the Dragon, this fascinating book ends by recognizing that we have enemies outside the Church as well—human enemies who oppose God because they are enslaved to lies and to demons, who are aligned with God’s enemy, Satan. God hears and remembers, not only delivering us from this danger, but even sustaining us by the hands of those who, like Habakkuk, await the return of the LORD, and call out “the righteous shall live by faith” (Hab 2:4).

Here, then, is a delightful and vivid tale of idols, monsters, and mob rule that can sway even a well-meaning king. Here is a story of exposé, dragon-slaying (without even a sword), and eating a hearty meal in the very teeth of danger. Here is a story that reminds us where to fix our eyes for help, and whom to worship: for He cares for every aspect of our lives, from our safety, to our vision of the truth, and even to our human needs. With Daniel, we can say, when necessary, to our own age, “Behold the things you have been worshipping.” With Daniel, we can be strengthened by the very food of God, brought to us in an even more costly manner than a harrowing flight from Judea to Babylon. The true bread of God is made available to us, of course, through the Cross! Most importantly, with Daniel, we can declare “I will worship the Lord my God, for He is the living God.”